Learning from Cao Cao, Hero of a Turbulent Age: The Art of Discerning Talent and Mastering Organizational Management

1. Introduction

John: Hello everyone, and welcome. Today, we’re delving into the life of one of Chinese history’s most compelling and controversial figures: Cao Cao (曹操). He lived from 155 to 220 AD, a period marking the decline of the Later Han Dynasty (後漢末期 – Hòu Hàn Mòqī) and the rise of the Three Kingdoms (三国時代 – Sānguó Shídài). Cao Cao was a warlord, a statesman, a brilliant strategist, and a poet. His legacy is complex; he’s often portrayed as both a hero and a villain.

Lila: It’s fascinating, John! I’ve heard his name associated with incredible strategic thinking and almost a kind of “charismatic manager” vibe, especially in the context of our theme today: “Learning Modern Management from Cao Cao, Hero of a Turbulent Age: The Art of Discerning Talent and Mastering Organizational Management.” I’m really curious to see what timeless lessons a figure from nearly two millennia ago can offer us, especially in areas like spotting talent and running an effective organization.

John: Precisely, Lila. Cao Cao’s era was one of immense upheaval and constant warfare – a “turbulent age” (乱世 – ransai) as the Japanese title suggests. Leaders who thrived in such conditions often possessed extraordinary skills in resource management, human psychology, and long-term planning. Our goal today is to provide a beginner-friendly introduction to his life and explore those very aspects, separating historical fact from later embellishments where possible.

2. Early Life & Family Background

John: Cao Cao was born in 155 AD in Qiao County, Pei Principality (沛國譙縣 – Pèi Guó Qiáo Xiàn), which is now Bozhou in Anhui province. His early life is quite interesting. His father, Cao Song (曹嵩), was the adopted son of Cao Teng (曹騰), a powerful and influential eunuch who served several Han emperors. This connection to the court eunuchs was significant.

Lila: A powerful eunuch grandfather? That sounds like it could be a double-edged sword. Did that give him a leg up, or was there a stigma attached, especially in a society that valued traditional family lines?

John: Both, potentially. Eunuchs, particularly in the Later Han, wielded considerable political power, and Cao Teng was highly respected, even by Confucian officials, which was unusual. This certainly provided Cao Song, and by extension Cao Cao, with connections and resources. Cao Song himself rose to the highest office in the imperial administration, Grand Commandant (太尉 – Tàiwèi). However, the eunuch faction was often viewed with suspicion and disdain by the scholar-official class, who saw them as corrupting influences. So, while Cao Cao benefited from his family’s status, he may have also faced prejudice from certain quarters. According to Chen Shou’s Records of the Three Kingdoms (三國志 – Sānguózhì), young Cao Cao was known for his cunning, his love of hunting and music, and a general disregard for strict societal conventions. Some contemporaries didn’t think much of him initially, but others recognized his potential early on.

Lila: So, a bit of a maverick from a young age, with a complex family background. That already paints a picture of someone who might not follow the conventional path to power.

John: Indeed. There’s a famous (though possibly apocryphal) story from the Shiyu (世語), cited by Pei Songzhi in his annotations to the Sanguozhi, that illustrates his youthful character. His uncle often complained to Cao Song about Cao Cao’s wild ways. To counter this, Cao Cao once feigned a fit in front of his uncle. When the uncle rushed to tell Cao Song, Cao Song found his son perfectly fine. Cao Cao then said, “I have never had such an illness, but I have lost the love of my uncle, and therefore he deceives you.” After this, Cao Song no longer believed his brother’s complaints, and Cao Cao became even more unrestrained. This story, whether entirely true or not, contributed to his reputation for cleverness and a willingness to use deception.

3. Key Events & Turning Points

John: Cao Cao’s career was marked by a series of pivotal events that shaped his rise. His formal entry into officialdom began when he was nominated as “Filial and Incorrupt” (孝廉 – xiàolián), a common path for aspiring officials, around the age of 20. He was then appointed District Magistrate of Luoyang North (洛陽北部尉 – Luòyáng Běibù Wèi), the capital’s northern district.

Lila: Luoyang, the imperial capital! That must have been a challenging first major post. How did he do?

John: He made an immediate impact by enforcing the law strictly, regardless of social standing. He famously had the uncle of a powerful eunuch flogged to death for violating the night curfew. This established his reputation for impartiality and courage, but also made him powerful enemies, leading to his “promotion” away from the capital to a less critical post. A key turning point was the Yellow Turban Rebellion (黃巾之亂 – Huángjīn zhī Luàn) in 184 AD. This massive peasant uprising destabilized the Han Dynasty significantly. Cao Cao served as a cavalry commander and distinguished himself in quelling the rebels, gaining valuable military experience and recognition.

John: The next major phase began with the tyranny of Dong Zhuo (董卓), a powerful warlord who seized control of Luoyang and the young Emperor Xian (獻帝 – Xiàn Dì) in 189 AD. Cao Cao refused to be part of Dong Zhuo’s regime. According to the Sanguozhi, he changed his name and escaped Luoyang. He then issued a call to arms, and a coalition of regional officials and warlords formed in 190 AD to challenge Dong Zhuo. Though the coalition eventually fractured due to internal rivalries, it marked Cao Cao’s emergence as an independent leader.

Lila: So he went from local official to a rebel leader, in a sense, against a usurping power. That’s quite a jump.

John: Yes, and a crucial one. He gradually built up his own power base, primarily in Yan Province (兗州 – Yǎnzhōu). A truly pivotal moment came in 196 AD. The Han court was in disarray, with Emperor Xian a fugitive. Cao Cao marched to Luoyang and “welcomed” the Emperor, escorting him to Xu (許昌 – Xǔchāng), which became the new capital under Cao Cao’s control. This strategic masterstroke allowed him to issue edicts in the Emperor’s name, giving him immense political legitimacy. This strategy is often described as “holding the Son of Heaven to command the regional lords” (挾天子以令諸侯 – xié Tiānzǐ yǐ lìng zhūhóu).

John: Another defining event was the Battle of Guandu (官渡之戰 – Guāndù zhī Zhàn) in 200 AD. Cao Cao, with a significantly smaller force, achieved a decisive victory over the powerful northern warlord Yuan Shao (袁紹). This battle, as detailed in the Sanguozhi, cemented his control over much of northern China and is a classic example of his strategic brilliance and ability to win against the odds through careful planning, deception, and exploiting enemy weaknesses.

Lila: Guandu sounds like a textbook case of strategic genius! But I’ve also heard of a major defeat for him – the Battle of Red Cliffs?

John: Indeed. The Battle of Red Cliffs (赤壁之戰 – Chìbì zhī Zhàn) in 208 AD was a significant setback. His attempt to conquer southern China was thwarted by the allied forces of Liu Bei (劉備) and Sun Quan (孫權). This defeat effectively ensured the division of China into three spheres of influence, leading to the Three Kingdoms period. Despite this, Cao Cao consolidated his power in the north. He was enfeoffed as the Duke of Wei (魏公 – Wèi Gōng) in 213 AD and then King of Wei (魏王 – Wèi Wáng) in 216 AD, granting him immense authority and laying the foundations for the state of Cao Wei (曹魏), which his son Cao Pi (曹丕) would formally establish after his death. Cao Cao himself died in Luoyang in 220 AD, never having taken the title of emperor.

4. Leadership Style / Philosophies / Personality Traits

John: Cao Cao’s leadership style was a fascinating blend of pragmatism, strategic foresight, and personal charisma, though not without its harsh aspects. One of his most defining philosophies, particularly relevant to our theme, was his approach to talent: “Appoint people on their merits, not their reputation or moral standing” (唯才是舉 – wéi cái shì jǔ). He issued several decrees explicitly stating his desire to recruit capable individuals, even if they had personal failings or came from humble backgrounds. This was a radical departure from the traditional emphasis on lineage and Confucian virtues alone.

Lila: That sounds incredibly modern! “Skills-based hiring,” almost. How did he put that into practice? It must have ruffled some feathers among the traditional elite.

John: It certainly did, but it was effective in attracting a wide range of talented individuals to his service. Men like Guo Jia (郭嘉), a brilliant but unconventional strategist, or Xun Yu (荀彧), a statesman from a prominent family who provided crucial advice, thrived under him. He was known to overlook past enmities or perceived moral lapses if someone possessed abilities he needed. This pragmatism extended to all areas of his governance. He was a strategic thinker of the highest order, known for his long-term vision and his ability to adapt plans to changing circumstances. His military genius is undisputed; he even wrote commentaries on Sun Tzu’s Art of War (孫子兵法 – Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ), some of which survive today.

John: In terms of personality, he was complex. He was known for strict military discipline. His implementation of the *tuntian* (屯田) system – agricultural colonies where soldiers and landless peasants cultivated land to supply the army and the state – was a masterstroke of logistical and social organization, as noted by historians like Rafe de Crespigny in Imperial Warlord: A Biography of Cao Cao 155-220 AD. This showed a concern for the welfare of his soldiers and the stability of his territories. He could be decisive and bold, willing to take calculated risks. He inspired fierce loyalty in many of his followers. Yet, he could also be ruthless, suspicious, and unforgiving, particularly when he felt betrayed or when his power was challenged.

Lila: So, a leader who valued results and loyalty, and wasn’t afraid to break with tradition to get the best people. That sounds like a powerful combination, especially in a chaotic era. What about his less “warlord-like” traits?

John: Beyond his military and political acumen, Cao Cao was a man of considerable literary talent. He was an accomplished poet, and his works are known for their directness, depth of feeling, and reflection on the transient nature of life and the suffering caused by war. This artistic side adds another layer to his personality, showing a capacity for introspection and a broader cultural engagement than one might expect from a typical warlord.

5. Famous Quotes or Decisions

John: Cao Cao’s pragmatic and sometimes controversial nature is reflected in sayings and decisions attributed to him. One of the most infamous quotes, “I would rather betray the world than let the world betray me” (寧我負人,毋人負我 – Nìng wǒ fù rén, wú rén fù wǒ), is widely known. However, it’s crucial to note that this particular phrasing and its common interpretation largely stem from the historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三國演義 – Sānguó Yǎnyì), in a specific, highly dramatized context involving the killing of Lü Boshe’s family. Historical sources like the Sanguozhi and its annotations present a more ambiguous or different event. While Cao Cao was certainly capable of ruthlessness, this quote as popularly understood is more a literary device than a historically verified personal motto.

Lila: That’s an important distinction! It shows how fiction can really shape our perception of historical figures. Are there quotes that are more historically grounded and reflect his leadership philosophy?

John: Yes, his edicts on talent recruitment are very telling. For instance, in one edict issued in 210 AD, he explicitly stated that he was looking for people with ability, even if they had flaws in their conduct, such as being “uncorrupt” or “disloyal” in the past, or even if they had “stains” on their reputation. This focus on practical ability over conventional virtue was revolutionary. Then there are his poems, which offer direct insight into his thoughts. His famous “Short Song Style” (短歌行 – Duǎn Gē Xíng) is a prime example. It contains lines like:

- “How to resolve my melancholy? Only Du Kang (a legendary brewer, meaning wine) will do.” (何以解憂,唯有杜康 – Héyǐ jiěyōu, wéi yǒu Dù Kāng)

- And, more directly related to his search for talent: “The mountains are never too high, the seas are never too deep. When the Duke of Zhou spat out his mouthful (to eagerly welcome worthy men), the hearts of all under Heaven inclined to him.” (山不厭高,海不厭深。周公吐哺,天下歸心 – Shān bù yàn gāo, hǎi bù yàn shēn. Zhōu Gōng tǔbǔ, tiānxià guīxīn.)

This poem clearly expresses his deep yearning for capable individuals to join his cause.

Lila: The poem is beautiful and quite poignant. It shows a much more reflective and aspirational side than the “betray the world” quote suggests. What about key decisions that defined his career?

John: Several stand out. As we mentioned, the decision to take Emperor Xian under his protection in 196 AD was a political masterstroke. It provided him with unparalleled legitimacy and a powerful tool to consolidate his authority. Another profoundly impactful decision was the widespread implementation of the *tuntian* agricultural system. This not only solved the critical problem of food supply for his armies and civilian population in war-torn regions but also brought vast tracts of abandoned land back into cultivation, contributing to economic recovery and social stability. It was a cornerstone of his state-building efforts. His conduct at the Battle of Guandu, choosing to make a daring raid on Yuan Shao’s supply depot at Wuchao (烏巢) based on intelligence from a defector, was a high-stakes gamble that paid off spectacularly, turning the tide of the campaign.

6. Influence on History (military, political, cultural, etc.)

John: Cao Cao’s influence on Chinese history is immense and multifaceted. Politically, he was instrumental in ending the widespread chaos that engulfed northern China during the collapse of the Han Dynasty. He restored a degree of order and effective governance over a vast territory. While he never formally usurped the Han throne, the powerful state of Wei (魏) that he established, and which his son Cao Pi later declared an empire, became one of the dominant Three Kingdoms. His administrative reforms and his system of governance laid a foundation that influenced subsequent dynasties.

Lila: So, a unifier and a state-builder, even if the complete unification of China didn’t happen in his lifetime. What about his military legacy?

John: Militarily, he was a genius. His campaigns are still studied for their strategic and tactical brilliance. As mentioned, he wrote commentaries on Sun Tzu’s Art of War, and these annotations are highly valued, demonstrating his deep understanding of military theory. He was an innovator in tactics and organization. The *tuntian* system, while primarily agricultural, also had significant military benefits by ensuring a stable supply chain and allowing armies to be self-sufficient in frontier regions. His military structures and emphasis on discipline were key to his success.

Lila: And you mentioned he was a poet! That’s not something you often associate with powerful warlords. How did he impact culture?

John: Culturally, Cao Cao was a significant figure. He, along with his sons Cao Pi (曹丕) and Cao Zhi (曹植), who were also gifted poets, became central figures of the Jian’an literary style (建安風骨 – Jiàn’ān fēnggǔ). This period, named after the Jian’an era (196-220 AD) of Emperor Xian’s reign, saw a flourishing of poetry characterized by its direct emotional expression, reflections on the harsh realities of the time, and a heroic spirit. Cao Cao’s patronage attracted many talented writers and scholars to his court, creating a vibrant intellectual atmosphere. His own poems are considered masterpieces and are still read and admired today for their vigor and poignancy. He helped to elevate the status of the five-character shi poetry (五言詩 – wǔyánshī).

John: His actions, policies, and the state he built directly shaped the political landscape of the Three Kingdoms period. The systems he put in place, particularly his emphasis on meritocracy in appointments and the *tuntian* system, had long-lasting effects on Chinese administration and land management, as extensively documented by scholars like Rafe de Crespigny in works such as Imperial Warlord.

7. Controversies & Historical Debates

John: Cao Cao is undoubtedly one of the most controversial figures in Chinese history. Much of his negative image, particularly in popular culture, can be traced to the influential 14th-century historical novel, Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三國演義 – Sānguó Yǎnyì) by Luo Guanzhong (羅貫中). This novel, which draws on historical events but heavily dramatizes them, often portrays Cao Cao as a cunning, cruel, and usurpacious tyrant, serving as the primary antagonist to the “virtuous” Liu Bei and the Shu-Han (蜀漢) state.

Lila: So, it’s a classic case of a good story shaping public perception, even if it’s not entirely accurate? Like some modern media portrayals that become more famous than the real events.

John: Precisely. It’s crucial for anyone studying Cao Cao to distinguish between the historical figure and his fictionalized counterpart. Chen Shou’s Records of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguozhi), written in the 3rd century, provides a more contemporary and balanced, though by no means uncritical, account. Chen Shou himself served the Jin Dynasty (晉朝 – Jìn Cháo), which succeeded Cao Wei, so his perspective is valuable. Even so, historical records do point to actions that are deeply troubling. A major stain on his record is the massacre in Xu Province (徐州 – Xúzhōu) in 193 AD. After his father Cao Song was murdered there (the circumstances are disputed, but it was believed to be by subordinates of Tao Qian (陶謙), the governor of Xu Province), Cao Cao launched a punitive invasion and carried out large-scale killings of civilians. This is recorded in several historical texts, including the Sanguozhi and the Book of the Later Han (後漢書 – Hòu Hàn Shū), and is an undeniable atrocity.

Lila: That’s horrific. It makes the “hero” label much more complicated. What other aspects of his rule are debated?

John: His treatment of Emperor Xian is a constant point of debate. Was he a loyal subject protecting the emperor from other ambitious warlords, or was he a manipulator who used the emperor as a puppet to legitimize his own power grabs? The strategy of “holding the Son of Heaven to command the regional lords” was undeniably effective for Cao Cao, but it drew criticism from contemporaries who saw him as overstepping his bounds and disrespecting the imperial authority he claimed to uphold. Another debate revolves around his ultimate ambition. Did he genuinely intend to remain a loyal minister of the Han, albeit an exceptionally powerful one, or was he biding his time to usurp the throne himself? He accepted the titles of Duke and then King of Wei, effectively ruling his own state within the Han empire, and adopted many imperial prerogatives. However, he never took the final step of declaring himself emperor, a title his son Cao Pi would claim shortly after Cao Cao’s death. Historians continue to analyze his motives and intentions.

Lila: So, a complex figure who can’t be easily painted as purely good or purely evil. The historical evidence itself presents a mixed picture.

John: Exactly. He operated in a brutal era where survival often necessitated harsh measures. Understanding him requires acknowledging both his remarkable achievements in restoring order and his capacity for ruthlessness.

8. Modern Lessons We Can Learn from Them

John: Drawing parallels between a 2nd-century warlord and modern management might seem like a stretch, but Cao Cao’s career offers some surprisingly relevant lessons, especially in line with the themes of “discerning talent” (人材を見抜く眼 – jinzai o minuku me) and “mastering organizational management” (組織運営の極意 – soshiki unei no gokui).

Lila: I’m eager to hear these! It’s what our Japanese title for this exploration focuses on. How can we apply his ancient wisdom today?

John: Firstly, let’s consider **Talent Management**. Cao Cao’s policy of “唯才是舉” (wéi cái shì jǔ) – promoting based on ability alone – is a powerful lesson. He actively sought out individuals with demonstrable skills, even if their backgrounds were unconventional or their past conduct questionable by traditional standards. In today’s competitive environment, organizations that can look beyond superficial qualifications or biases to identify and nurture genuine talent, regardless of where it comes from, have a distinct advantage. He understood that diverse skills were needed to build a strong state.

John: Secondly, his **Strategic Thinking** (戦略的思考 – senryakuteki shikō) is exemplary. Cao Cao was a master of long-term planning. He had a clear vision – the unification of China under a stable government – and he pursued it relentlessly. Yet, he was also highly adaptable. His victory at Guandu showed meticulous planning and the ability to seize unexpected opportunities. His defeat at Red Cliffs, while a setback, didn’t break him; he adjusted his strategy to consolidate his power in the north. Modern leaders need this combination of long-range vision and tactical flexibility to navigate an ever-changing business landscape.

Lila: That adaptability is key. Sometimes the best-laid plans go awry, and it’s how you react that matters. What about leadership in tough times – the “hero of a turbulent age” (乱世の英雄 – ransei no eiyū) aspect?

John: Absolutely. **Leadership in Crisis** is another area. Cao Cao rose to prominence during a period of almost complete societal breakdown. He demonstrated decisiveness, the ability to restore order from chaos, and remarkable resilience. He wasn’t afraid to make tough decisions. Modern leaders often face crises – economic downturns, market disruptions, internal challenges – and Cao Cao’s ability to maintain focus, rally his people, and find solutions in extreme adversity offers valuable insights. His emphasis on discipline and clear objectives was crucial in such times.

John: Finally, there’s **Organizational Management**. The *tuntian* system is a brilliant example of resource management and building a self-sufficient organization. He understood that a strong army and a stable state required a solid economic foundation. He built an effective administrative and military machine, with clear lines of command and a focus on efficiency. For modern businesses, this translates to creating sustainable operational models, ensuring resource security, and building robust organizational structures that can support growth and withstand pressure.

Lila: These are all incredibly relevant. The idea of looking past traditional markers for talent, being strategically agile, leading decisively in a crisis, and building a sustainable organization – these are timeless principles for any leader or manager.

John: Indeed. His pragmatism, his willingness to innovate, and his relentless pursuit of his goals, tempered with an understanding of human nature (both its strengths and weaknesses), make him a figure worth studying for anyone in a leadership position.

9. Fun Facts / Lesser-known Stories

John: Beyond the grand sweep of his military campaigns and political maneuvers, there are some interesting, lesser-known stories and facts about Cao Cao that add color to his personality, though some border on legend and should be treated with caution.

Lila: Oh, I love these kinds of details! They often make historical figures feel more human. What have you got?

John: Well, there’s a famous story, likely from Liu Yiqing’s Shishuo Xinyu (世說新語 – A New Account of Tales of the World), a collection of anecdotes about historical figures. (Legend says) When Cao Cao was due to receive an envoy from the Xiongnu (匈奴 – a powerful nomadic confederation to the north), he felt his own physical appearance was not imposing enough to impress the “barbarian” ambassador. So, he arranged for Cui Yan (崔琰), a famously handsome and dignified official, to impersonate him on the throne, while Cao Cao himself stood beside him, dressed as a sword-bearing attendant. After the audience, Cao Cao sent someone to ask the envoy, “What did you think of the King of Wei?” The envoy replied, “The King is certainly elegant and distinguished. However, the attendant holding the sword by his side – he is the true hero!” (Legend says) Cao Cao, hearing this, feared the envoy’s perceptiveness and had him pursued and killed.

Lila: Wow, that’s a dramatic story! If true, it speaks volumes about his cunning, his awareness of perception, and also a streak of ruthlessness. Quite a mix!

John: It is, and it certainly contributes to his complex image. On a different note, despite the vast wealth and power he accumulated, some historical accounts suggest Cao Cao advocated for and practiced a degree of frugality in his personal life and court, condemning extravagance. He also issued specific instructions for his own burial: it was to be simple, in unadorned ground, without gold or jade treasures, so as not to attract tomb raiders. This was quite unusual for a ruler of his stature at the time.

Lila: That’s a fascinating contrast to the typical image of powerful rulers building lavish tombs. Did they find his tomb?

John: Yes, in 2009, archaeologists in Anyang, Henan Province, announced the discovery of a large tomb complex that they identified as Cao Cao’s Mausoleum (高陵 – Gāolíng). The identification was initially met with some scholarly debate, but further evidence, including inscribed tablets and the simplicity of the burial compared to imperial tombs, has led to a general acceptance by mainstream academia. The findings from the tomb are providing valuable insights into his life, the burial customs of the period, and have largely corroborated his instructions for a relatively simple interment.

John: Another interesting aspect is his intellectual curiosity beyond military matters and poetry. He is said to have written on various subjects, including strategy (as we know from his Sun Tzu commentary), and possibly even on governance and ethics, though most of these works are lost. He valued scholarship and gathered many learned men around him, fostering an environment of intellectual exchange.

10. Recommended Books / Films / Museums / Historic Sites

John: For those interested in learning more about Cao Cao and his era, there’s a wealth of resources available, ranging from primary historical texts to modern scholarship and popular media.

Lila: That’s great! Where should a beginner start, and what’s good for a deeper dive?

John: For **Books**:

- The foundational historical text is Chen Shou’s Records of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguozhi). It’s a challenging read for beginners but is the principal source. Annotated translations exist.

- For authoritative modern scholarship in English, Professor Rafe de Crespigny’s works are indispensable. His Imperial Warlord: A Biography of Cao Cao 155-220 AD (Brill, 2010) is the definitive biography. He has also translated relevant sections of Sima Guang’s Zizhi Tongjian (資治通鑑 – Comprehensive Mirror to Aid in Government) in To Establish Peace: Being the Chronicle of the Later Han Dynasty for the Years 189 to 220 AD (ANU, 1996), which provides extensive narrative detail.

- And of course, one must mention Luo Guanzhong’s Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo Yanyi). It’s a novel, not a history book, but it’s profoundly shaped the popular understanding of Cao Cao and the entire period. Read it for the epic story, but always with the caveat that it’s a dramatization with a clear pro-Liu Bei bias.

Lila: What about films or TV series? Sometimes those can be a good entry point, even if they take liberties.

John: Absolutely. Visual media can bring the era to life.

- John Woo’s two-part film Red Cliff (2008-2009) is a spectacular depiction of the famous battle, though it heavily fictionalizes many aspects and characters. Zhang Fengyi plays Cao Cao.

- The Chinese television series Three Kingdoms (2010) is a much more comprehensive adaptation of the novel and historical events. Chen Jianbin’s portrayal of Cao Cao in this series is widely acclaimed for its depth and nuance.

- Another excellent recent series is The Advisors Alliance (軍師聯盟 – Jūnshī Liánméng, 2017), which focuses on Cao Cao’s strategist Sima Yi (司馬懿) but features a powerful depiction of Cao Cao in his later years, played by Yu Hewei.

Remember, these are dramatizations, but they can spark interest in the historical figures.

Lila: And for those who might have the chance to travel or explore museum collections?

John:

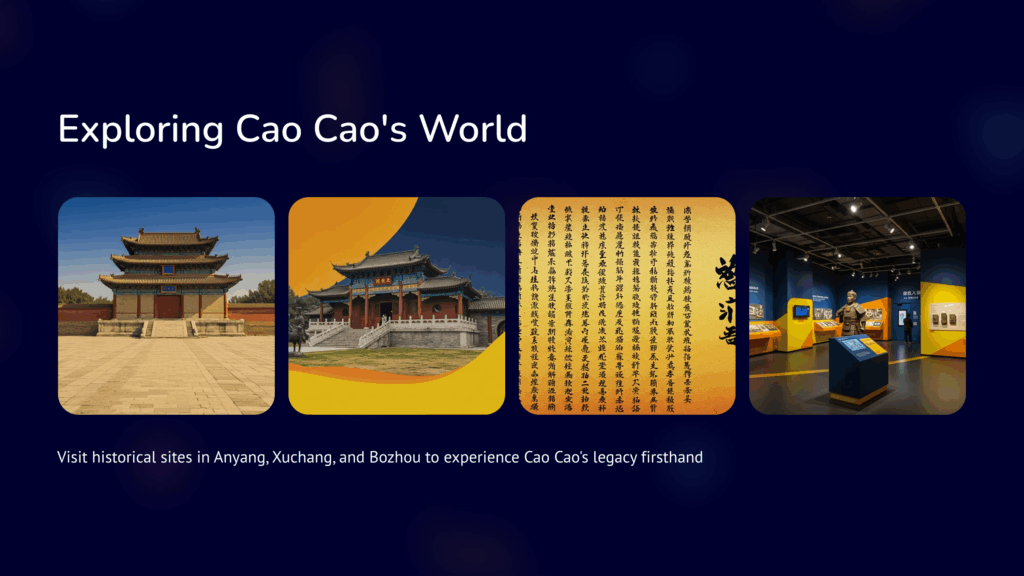

- The most significant site is undoubtedly **Cao Cao’s Mausoleum (Gaoling – 高陵)** in Anyang, Henan Province, China. While public access to the core tomb might be restricted, there are often associated visitor centers or exhibitions.

- Cities like **Xuchang** (Henan Province), which served as Cao Cao’s capital, and **Bozhou** (Anhui Province), his birthplace, have museums and historical sites related to him and the Three Kingdoms period. For example, the Xuchang Museum often has exhibits.

- Major provincial and national museums in China, such as the National Museum of China in Beijing or the Henan Museum in Zhengzhou, will have artifacts from the Han Dynasty and Three Kingdoms period that provide context.

11. Summary / Closing Thoughts

John: To summarize, Cao Cao was a monumental figure who profoundly shaped one of the most turbulent and formative periods in Chinese history. He rose from a relatively modest background to become the most powerful man in China, effectively ending the Han Dynasty’s decline in the north and laying the groundwork for the state of Cao Wei. He was a brilliant military strategist, a capable administrator, a pragmatic leader who valued talent above all else, and a gifted poet.

Lila: He certainly defies easy categorization, doesn’t he? Neither a simple hero nor an outright villain, but a complex individual who navigated incredibly challenging times with a mix of genius, ruthlessness, and vision. The lessons in leadership, particularly around talent spotting and strategic adaptability, feel surprisingly fresh and relevant even today.

John: Indeed. His legacy is a testament to his extraordinary abilities. While controversies surrounding his methods and motives will likely continue, his impact as a unifier, a reformer, and a cultural patron is undeniable. He was a man who not only responded to the chaos of his era but actively shaped its outcome. Chen Shou, the historian who knew the world Cao Cao came from, summarized him in the Sanguozhi as “a very extraordinary man, and a hero who was head and shoulders above his common contemporaries.” (非常之人,超世之傑 – fēicháng zhī rén, chāoshì zhī jié).

Lila: “A hero head and shoulders above his contemporaries.” That’s quite an endorsement from a historian of the time. It really makes you think about the kind of indelible mark some leaders can leave on history. Thank you, John, this has been incredibly insightful.

John: You’re most welcome, Lila. Cao Cao’s story reminds us that history is often found in shades of grey, and that even figures from the distant past can offer profound lessons for our own times.

12. References & Further Reading

- Chen Shou (陳壽). Sanguozhi (三國志 – Records of the Three Kingdoms). (Primary historical source).

- Pei Songzhi (裴松之). Annotations to the Sanguozhi. (Provides crucial supplementary information and alternative accounts).

- De Crespigny, Rafe. A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD). Leiden: Brill, 2007.

- De Crespigny, Rafe. Imperial Warlord: A Biography of Cao Cao 155-220 AD. Leiden: Brill, 2010. (Key scholarly biography).

- De Crespigny, Rafe. To Establish Peace: Being the Chronicle of the Later Han Dynasty for the Years 189 to 220 AD as Recorded in Chapters 59 to 69 of the Zizhi Tongjian of Sima Guang. Faculty of Asian Studies Monographs, New Series No. 21. Canberra: Australian National University, 1996. (Translation of key historical narrative).

- Luo Guanzhong (羅貫中). Sanguo Yanyi (三國演義 – Romance of the Three Kingdoms). (Influential historical novel, treat with caution for historical accuracy).

- Liu Yiqing (劉義慶). Shishuo Xinyu (世說新語 – A New Account of Tales of the World). (Source for many anecdotes, some legendary).

- Fan Ye (范曄). Hou Hanshu (後漢書 – Book of the Later Han). (Historical record for the Later Han period).