Unpacking the Legacy of Toyotomi Hideyoshi: A Study in Ambition and Acumen

John: Welcome, everyone, to our exploration of one of Japan’s most pivotal historical figures. Today, we’re delving into the life of Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣秀吉), a man whose journey from peasant to the de facto ruler of Japan is nothing short of extraordinary. He’s a central figure in understanding the late Sengoku period (戦国時代 – Warring States period, c. 1467 – c. 1615) and the subsequent unification of the country.

Lila: I’m really looking forward to this, John. Hideyoshi is such a fascinating character! From what I’ve read, he’s often portrayed as incredibly shrewd, especially in how he managed people and built his power base, particularly in Osaka. His skills in what the Japanese call 人心掌握術 (*jinshin shōakujutsu* – the art of capturing people’s hearts and minds) seem legendary. How did someone from such humble beginnings achieve so much?

Introduction

John: That’s the crux of his story, Lila. Toyotomi Hideyoshi, originally named Hiyoshi-maru (日吉丸) and later Kinoshita Tōkichirō (木下藤吉郎), rose during a time of immense social upheaval and constant warfare. His life is a testament to ambition, strategic thinking, and an almost unparalleled ability to understand and influence others. He didn’t come from samurai (侍 – warrior class) lineage, which makes his ascent all the more remarkable. He essentially ended the century-long civil war and laid the groundwork for the Tokugawa Shogunate that followed.

Lila: So, he was a unifier, but not from the traditional warrior elite. That must have required incredible communication skills and a knack for networking, especially in a society as hierarchical as feudal Japan. It sounds like a masterclass in flexibility and seizing opportunities!

John: Precisely. His story isn’t just about battles and politics; it’s about a unique personality who could charm, negotiate, and, when necessary, intimidate his way to the top. We’ll be looking at his methods, his impact, and what we can still learn from him today, particularly concerning those qualities you mentioned: his communication, networking, flexibility, and his ability to win over the people, especially in a bustling hub like Osaka.

Early Life & Family Background

John: Hideyoshi’s origins are quite modest, and some details are shrouded in a bit of legend. He was born in 1537 (though some sources say 1536) in Nakamura, Owari Province (尾張国 – present-day western Aichi Prefecture). His father, Yaemon (弥右衛門), was an ashigaru (足軽 – a peasant foot-soldier) or farmer. This background is crucial; he had no inherited status or wealth.

Lila: Wow, so he truly started from the bottom. What was family life like for him? Did he have siblings?

John: His father died when Hideyoshi was young, around the age of seven. His mother later remarried a man named Chikuami (竹阿弥), who was apparently not very fond of Hideyoshi. He had an older sister, Tomo (とも), who married Soeda Jinbae (副田甚兵衛), and a younger half-brother, Hidenaga (秀長), born from his mother’s second marriage. Hidenaga would later become one of Hideyoshi’s most trusted and capable deputies. There was also a younger half-sister, Asahi (朝日姫), who played a role in his political marriages.

Lila: So, not exactly a privileged upbringing. It’s often said that adversity shapes character. Do we know much about his childhood beyond that?

John: Details are sparse and often embellished in later accounts, such as the *Taikōki* (太閤記 – a biography of Hideyoshi). (Legend says) he was sent to a temple as a boy but ran away, preferring a life of adventure. He’s often described as small, thin, and with monkey-like features, earning him the early nickname Kozaru (小猿 – “little monkey”), supposedly given by Oda Nobunaga. While these descriptions might have elements of truth, they also fit into a narrative of an unconventional hero. What is clear is that he left home at a young age to seek his fortune.

John: According to the *Nihonshi* (日本史 – History of Japan) by Luís Fróis, a Jesuit missionary in Japan at the time, Hideyoshi was described as having six fingers on one hand. Fróis noted, “He was a man of small stature, and he was ugly and had six fingers on one hand.” This is a detail corroborated by a contemporary European source, though some Japanese accounts don’t emphasize it.

Lila: Six fingers? That’s an interesting detail! It makes him even more distinct. It’s amazing how these small, personal details humanize such monumental figures.

Key Events & Turning Points

John: Hideyoshi’s career truly began when he entered the service of Imagawa Yoshimoto (今川義元), a powerful daimyō (大名 – feudal lord). However, he soon left and, around 1558, managed to gain a position as a sandal-bearer for Oda Nobunaga (織田信長), one of the most powerful warlords of the time. This was a very lowly position, but it put him in Nobunaga’s orbit.

Lila: The famous sandal-bearer! (Legend says) he warmed Nobunaga’s sandals in his robe during cold weather. Is there truth to that, or is it more of a symbolic story of his dedication?

John: It’s one of those anecdotes that perfectly encapsulates his perceived ingenuity and desire to please, but its literal truth is difficult to verify. It appears in later hagiographies. What is certain, as noted in “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 4,” is that Hideyoshi quickly proved his worth through intelligence and resourcefulness. He excelled at various tasks, from logistics and supply management to supervising construction projects, like the emergency repairs at Kiyosu Castle (清洲城).

John: A key turning point was his role in the Siege of Inabayama Castle (稲葉山城) in 1567. Hideyoshi was instrumental in finding a secret route into the supposedly impregnable castle, and (legend says) he also played a key role in bribing enemy samurai to switch sides. This victory gave Nobunaga control of Mino Province (美濃国) and significantly raised Hideyoshi’s standing. He was then allowed to use the name Hashiba Hideyoshi (羽柴秀吉), combining characters from two of Nobunaga’s most senior retainers, Niwa Nagahide (丹羽長秀) and Shibata Katsuie (柴田勝家).

Lila: That’s clever networking right there – even in choosing a name! What happened after Nobunaga’s death? That must have been a massive upheaval.

John: Indeed. Nobunaga was assassinated by Akechi Mitsuhide (明智光秀) in the Honnō-ji Incident (本能寺の変) in 1582. Hideyoshi was then campaigning against the Mōri clan (毛利氏) in the Chūgoku region (中国地方 – western Honshu). Upon hearing the news, he displayed incredible speed and decisiveness. He quickly made peace with the Mōri – a strategic masterstroke – and force-marched his army back towards Kyoto. This is known as the *Chūgoku Ōgaeshi* (中国大返し – Great Chūgoku Return). Within days, he confronted and defeated Akechi Mitsuhide at the Battle of Yamazaki (山崎の戦い). This swift action positioned him as Nobunaga’s avenger and a primary contender for his power.

Lila: That sounds incredibly risky – making peace with an enemy to rush back. Talk about flexibility and quick thinking! What came next in his path to ultimate power?

John: Following Yamazaki, there was a power struggle among Nobunaga’s former vassals. Hideyoshi clashed with Shibata Katsuie, Nobunaga’s most senior general, at the Battle of Shizugatake (賤ヶ岳の戦い) in 1583. Hideyoshi’s victory there cemented his dominance. He then began the construction of Osaka Castle (大坂城) on the site of the Ishiyama Hongan-ji (石山本願寺), a fortress temple Nobunaga had struggled for years to conquer. This was a hugely symbolic move, establishing his new power base. By 1590, after the successful Siege of Odawara (小田原征伐) against the Hōjō clan (北条氏), he had effectively unified Japan, a feat that had eluded warlords for over a century.

Lila: Osaka Castle! That’s such an iconic landmark. Building it there must have sent a powerful message about his control and his vision for the future.

Leadership Style / Philosophies / Personality Traits

John: Hideyoshi’s leadership was a fascinating blend of traits. As you mentioned, Lila, his *jinshin shōakujutsu* was central. He had an uncanny ability to read people, understand their motivations, and win their loyalty or, at least, their compliance. This is well-documented in many historical accounts, including contemporary letters and observations. He wasn’t afraid to use charm, lavish gifts, promotions, or even strategic marriages to build alliances.

Lila: So, he was a master networker and communicator. How did this manifest in practice? Was he a smooth talker?

John: He could be incredibly persuasive. He often preferred negotiation to outright conflict, if possible. For example, before major sieges, he would frequently try to convince opponents to surrender by offering generous terms or highlighting the futility of resistance. His correspondence shows a man who could adapt his tone – from friendly and cajoling to stern and demanding – depending on the audience. He understood the power of information and employed a sophisticated intelligence network.

John: His flexibility was another key trait. Coming from a peasant background, he wasn’t rigidly bound by samurai traditions or codes of conduct in the same way some of his contemporaries were. He was pragmatic and opportunistic. If a plan wasn’t working, he could pivot quickly. This adaptability was crucial in the ever-shifting alliances of the Sengoku period. For instance, his rapid truce with the Mōri before Yamazaki is a prime example.

Lila: That makes sense. Someone less flexible might have been too proud to make peace with an enemy so quickly. What about his personality? He sounds quite charismatic, but was there a darker side?

John: He was certainly ambitious, and as he gained more power, some historians, like George Sansom in “A History of Japan, 1334-1615,” note an increasing tendency towards grandiosity and, at times, ruthlessness. He enjoyed ostentatious displays of wealth and power, like the grand Golden Tea Room (黄金の茶室 – *Ōgon no chashitsu*) or the lavish parties he threw at his Jurakudai (聚楽第) palace in Kyoto. Yet, he also cultivated an image of generosity, distributing land and rewards to loyal vassals, which was essential for maintaining his power base.

Lila: It sounds like he understood branding and public relations, even back then! Especially in a major commercial center like Osaka, being able to project an image of both power and generosity must have been vital for keeping the populace on his side.

John: Absolutely. His ability to connect with diverse groups – from powerful daimyō to merchants and even commoners – was a hallmark of his rule. He recognized the growing importance of the merchant class and fostered trade, which benefited Osaka tremendously. He was also known for his quick wit and, at times, a surprisingly informal demeanor, which could disarm people. However, this could also be a calculated persona.

Famous Quotes or Decisions

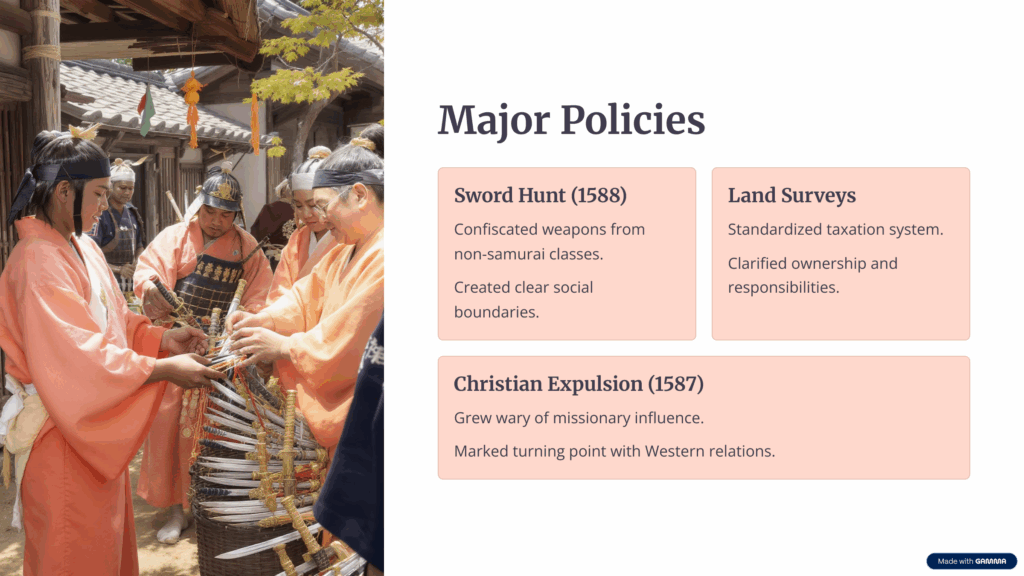

John: While direct, verbatim quotes from that period can be tricky to authenticate perfectly, as many are recorded in later chronicles, certain phrases and decisions are strongly attributed to him and reflect his thinking. One of his most impactful decisions was the **Sword Hunt (刀狩り – *katanagari*)** of 1588. He ordered the confiscation of weapons from the peasantry and anyone not of the samurai class.

Lila: The Sword Hunt – I’ve heard of that. What was the main reason behind it? Was it just about disarming potential rebels?

John: That was a primary motivation, certainly. The official edict stated the metal would be melted down to construct a giant statue of Buddha for the Hōkō-ji temple (方広寺) in Kyoto, thus earning merit for the populace in the afterlife. However, historians widely agree that its main purpose was to solidify social order, prevent peasant uprisings (百姓一揆 – *hyakushō ikki*), and clearly demarcate the samurai as the sole armed class. This, combined with his land surveys, aimed to create a more stable, controllable society. Mary Elizabeth Berry, in her book “Hideyoshi,” analyzes these policies as fundamental to his state-building efforts.

Lila: So, it was a social engineering project as much as a security measure. What other major decisions define his rule?

John: The **Taikō Kenchi (太閤検地 – the Taikō’s land surveys)**, conducted systematically from the 1580s onwards, was another monumental undertaking. (“Taikō” 太閤 was a title for a retired regent, which Hideyoshi took). These surveys assessed the agricultural productivity of land across Japan. This allowed for a more standardized and efficient system of taxation, with taxes based on the assessed yield (*kokudaka* 石高 – measured in koku, a unit of rice). It also clarified land ownership and responsibilities, tying peasants to their land and daimyō to their domains.

Lila: That sounds incredibly bureaucratic for the era. It must have given him immense control over the country’s resources.

John: It did. It fundamentally reshaped the economic and social landscape of Japan. Another significant, though perhaps less a single “decision” and more a policy, was his **expulsion edict against Christian missionaries in 1587 (伴天連追放令 – *bateren tsuihōrei*)**. While initially tolerant, Hideyoshi grew wary of the missionaries’ influence and their potential links to European colonial ambitions. Though not always strictly enforced immediately, it marked a turning point in Japan’s relationship with the West for that period.

John: One often-cited, though perhaps apocryphal, quote attributed to him regarding his ambition and methods is: “If the cuckoo does not sing, I will make it sing.” This is often contrasted with Oda Nobunaga (“If the cuckoo does not sing, kill it”) and Tokugawa Ieyasu (“If the cuckoo does not sing, I will wait for it to sing”). While its origins are more folklore, it neatly encapsulates his proactive, can-do, and sometimes forceful approach to achieving his goals.

Lila: Those cuckoo comparisons are famous! They really do give a snapshot of their supposed personalities. Hideyoshi’s version certainly points to his belief in his own agency and his skill in making things happen.

Influence on History (Military, Political, Cultural, etc.)

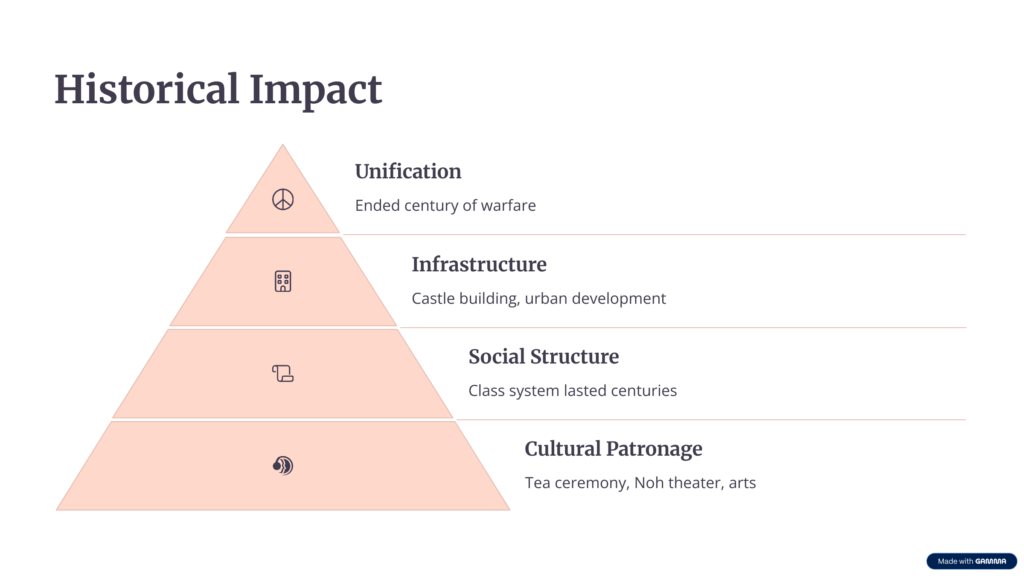

John: Hideyoshi’s influence on Japanese history is profound and multifaceted. Politically, his greatest achievement was the **unification of Japan**. After more than a century of endemic warfare, he brought the warring daimyō under a single authority. This laid the essential groundwork for the over 250 years of peace under the Tokugawa Shogunate that followed his death. As historian Conrad Totman discusses in “Japan Before Perry,” Hideyoshi’s unification was a pivotal moment.

Lila: So, without Hideyoshi, the Tokugawa era might not have happened, or at least not in the same way?

John: It’s highly probable. Militarily, while he was a skilled commander, his long-term military legacy is perhaps more about consolidation than innovation. His large-scale campaigns, like the subjugation of Kyūshū (九州) and the Odawara campaign, demonstrated his logistical prowess and ability to mobilize massive armies. His **castle building**, particularly Osaka Castle, set new standards for scale and defensive design. These castles weren’t just military strongholds; they were also powerful symbols of authority and centers of administration and commerce.

Lila: Osaka Castle definitely stands out. What about his cultural impact? You mentioned his Golden Tea Room earlier.

John: Culturally, Hideyoshi was a significant patron of the arts, though his taste often leaned towards the opulent and magnificent, contrasting with the more restrained aesthetics favored by some, like Sen no Rikyū (千利休), the master of the tea ceremony (茶の湯 – *chanoyu*). Hideyoshi was an avid practitioner and promoter of the tea ceremony. He hosted grand tea parties, like the Kitano Grand Tea Ceremony (北野大茶湯 – *Kitano Ōchanoyu*) in 1587, to which people from all social classes were invited (though they had to bring their own tea utensils). This event aimed to showcase his cultural sophistication and his connection with the populace. He also patronized Noh theater (能) and painting, particularly the lavish style of the Kanō school (狩野派).

John: Socially, as we discussed with the Sword Hunt and land surveys, he implemented policies that led to a more rigid **class structure**. The separation between the samurai warrior class and the peasantry became more defined. This system, known as *heinō bunri* (兵農分離 – separation of warriors and farmers), aimed to create a stable social order, with each class fulfilling specific roles. This structure largely persisted into the Edo period.

Lila: It seems like he reshaped almost every aspect of Japanese society at the time. His impact on Osaka specifically, by making it his main stronghold, must have been huge for the city’s development too.

John: Absolutely. By choosing the location of the former Ishiyama Hongan-ji for Osaka Castle, he recognized its strategic importance – both militarily and economically, with its access to waterways and trade. His development of the castle town attracted merchants and artisans, turning Osaka into a major commercial and political hub. The city’s prosperity in the following centuries owes a great deal to the foundations Hideyoshi laid. His ability to manage and motivate the diverse population of a burgeoning city like Osaka showcases his *jinshin shōakujutsu* on a grand scale.

Controversies & Historical Debates

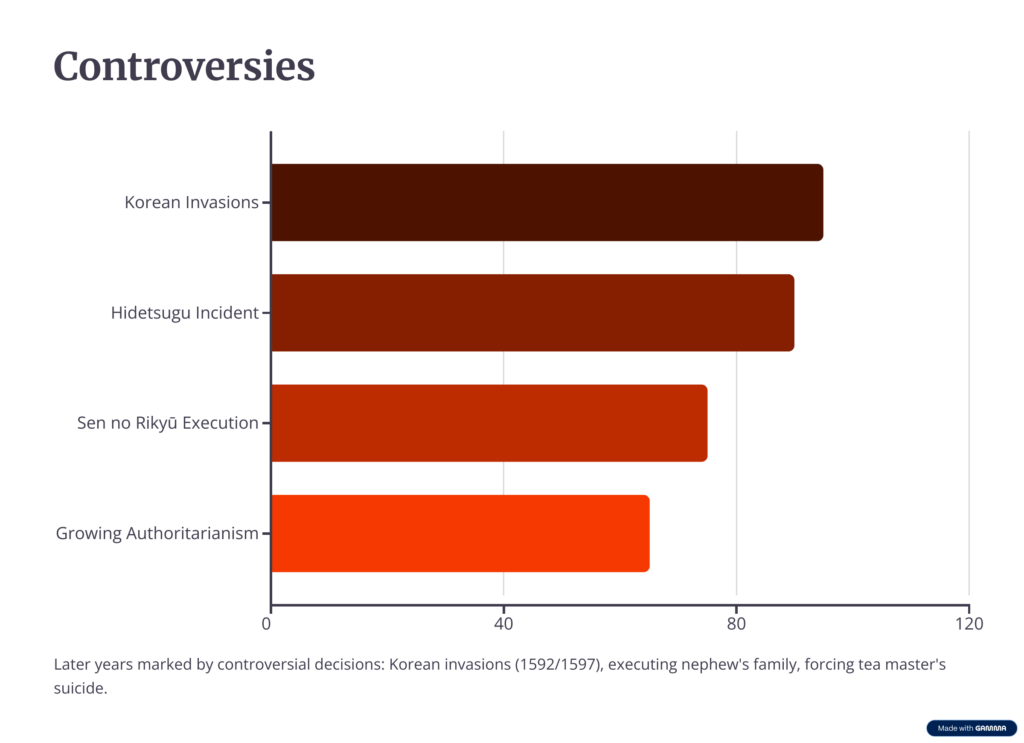

John: Despite his monumental achievements, Hideyoshi’s legacy is also marked by significant controversies. Perhaps the most criticized aspect of his later years were the **invasions of Korea (文禄・慶長の役 – *Bunroku-Keichō no eki*)** in 1592 and 1597. His motivations for these massive, costly campaigns are still debated by historians. Some suggest it was a way to redirect the energies of the now-unified samurai class, others point to megalomaniacal ambitions of conquering China, or securing his legacy.

Lila: Those invasions were devastating for Korea, weren’t they? And ultimately unsuccessful for Japan.

John: Precisely. They caused immense suffering and destruction in Korea, strained Japan’s resources, and ultimately failed to achieve their objectives. Many daimyō were reluctant participants, and the campaigns ended with Hideyoshi’s death in 1598. This venture is a dark stain on his record and a point of historical tension even today.

John: Another deeply controversial episode is the **Hidetsugu Incident (秀次事件 – *Hidetsugu jiken*)** in 1595. Hideyoshi had adopted his nephew, Toyotomi Hidetsugu (豊臣秀次), as his heir and appointed him Kanpaku (関白 – Imperial Regent), the title Hideyoshi himself held. However, after Hideyoshi’s own son, Hideyori (秀頼), was born in 1593, Hidetsugu’s position became precarious. In 1595, Hideyoshi accused Hidetsugu of treason and ordered him to commit seppuku (切腹 – ritual suicide). Not only that, but Hidetsugu’s entire family, including his wives, concubines, and young children, were executed. This brutality shocked many at the time and is often seen as a sign of Hideyoshi’s increasing paranoia or ruthlessness in his later years.

Lila: That’s horrific. To kill an entire family, including children… it paints a very different picture from the shrewd charmer.

John: It does. It highlights the complexities and contradictions in his character. There’s also the debate around his relationship with **Sen no Rikyū**, the tea master. Rikyū was a close confidant and cultural advisor to Hideyoshi. However, in 1591, Hideyoshi ordered Rikyū to commit seppuku. The exact reasons remain a subject of historical speculation – perhaps Rikyū had grown too influential, or there was a clash of aesthetic or political views, or (legend says) an issue over the placement of a statue of Rikyū at Daitoku-ji temple (大徳寺). This event demonstrated Hideyoshi’s capacity for absolute power and, some argue, a growing intolerance.

Lila: It seems like as he got older and more powerful, some of his earlier flexibility and charm might have given way to something harder and more autocratic.

John: That’s a common interpretation. Historians like Wakita Osamu, in studies on Hideyoshi’s regime, point to a consolidation of power that became increasingly authoritarian. His desire to establish a lasting Toyotomi dynasty, especially after the birth of Hideyori, likely fueled some of these more extreme actions as he sought to eliminate any potential threats, real or perceived.

Modern Lessons We Can Learn from Them

John: Despite the controversies, Hideyoshi’s life offers several enduring lessons, especially in the areas you highlighted earlier, Lila: communication, networking, flexibility, and understanding people – his *jinshin shōakujutsu*.

Lila: I can definitely see that. His rise from nothing is a huge lesson in itself. What would you say is the top takeaway in terms of **networking and communication**?

John: The power of building genuine connections and understanding diverse motivations. Hideyoshi didn’t just command; he persuaded, negotiated, and often co-opted potential rivals. He knew how to tailor his message. In a modern context, whether in business, politics, or even personal life, the ability to effectively communicate with different types of people and build a strong, supportive network is invaluable. He showed that who you know, and how well you can engage with them, can be as important as what you know.

Lila: That’s so true. We talk about “emotional intelligence” today, and it sounds like Hideyoshi was a master of it. What about **flexibility and adaptability**?

John: His entire career was a masterclass in this. He constantly adapted to changing circumstances. The *Chūgoku Ōgaeshi* is a prime example – turning a potential disaster (Nobunaga’s death) into a massive opportunity by quickly changing plans. In today’s fast-paced world, the ability to pivot, embrace change, and find solutions in unexpected situations is a critical skill. Hideyoshi wasn’t afraid to deviate from the conventional path if a better one presented itself.

John: Then there’s the lesson of **ambition tempered by pragmatism** (at least in his earlier and middle career). He had immense ambition, but he often pursued it through calculated steps, understanding the political landscape and the limits of his power at any given time. While his later ambition arguably overreached, his initial ascent shows the power of setting high goals and working strategically towards them.

Lila: And his understanding of **人心掌握術 (*jinshin shōakujutsu*)** – capturing hearts and minds – seems particularly relevant. How can we apply that today without being manipulative?

John: It’s about empathy and genuine engagement. For Hideyoshi, it meant understanding what his vassals, allies, or even common people desired or feared. In a modern leadership context, it translates to truly listening to your team, understanding their needs, and inspiring loyalty through respect and by providing opportunities for growth. It’s about creating a vision that people can believe in and want to be a part of. His focus on Osaka, developing it and trying to win over its diverse populace, shows an understanding that power isn’t just about force, but also about popular support and economic strength.

Lila: So, it’s less about manipulation and more about authentic leadership and creating buy-in. Even the darker aspects of his story, like the overreach with the Korean invasions or the Hidetsugu incident, offer a cautionary tale about unchecked ambition and the potential for power to corrupt.

John: Precisely. His life provides both positive examples and warnings. The importance of maintaining one’s core values and not letting power lead to paranoia or cruelty is a timeless lesson.

Fun Facts / Lesser-known Stories

John: Beyond the grand historical narrative, there are some interesting, sometimes anecdotal, aspects to Hideyoshi’s life. We’ve mentioned the story of him **warming Nobunaga’s sandals** (legend says). While its historicity is debated, it perfectly illustrates his eagerness to serve and his cleverness in gaining attention.

Lila: I love that story! It’s so vivid. What else is there?

John: (Legend says) Hideyoshi had a childhood name, **Hiyoshi-maru (日吉丸)**, which means “Sunshine Boy” or “Good Fortune Boy,” supposedly related to a dream his mother had involving the sun. This imagery of the sun became a recurring motif associated with him, perhaps symbolizing his rise and brilliance. His later family name, Toyotomi, can be translated as “Abundant Minister,” a name bestowed by the Emperor.

John: Another interesting point is his **patronage of Noh theater**. He was not just a spectator; he actively learned and performed Noh plays himself, even writing some. He would sometimes perform for the Emperor or his daimyō. This was quite unusual for a ruler of his stature and shows a different side to his personality, perhaps a desire for cultural legitimacy or simply a personal passion.

Lila: Him performing Noh? That’s quite a picture! It makes him seem more human and less like a purely political or military machine.

John: Indeed. And despite his immense power, he always seemed aware of his humble origins. (Legend says) he once told a story about his youth, when he was so poor he had to use a gourd as a water flask. This gourd, the *sennari byōtan* (千成瓢箪 – thousand-gourd), became one of his famous battle standards (馬印 – *uma-jirushi*). Each time he won a battle, another gourd was supposedly added. This symbol of his success from humble beginnings was a powerful part of his personal mythology.

Lila: The thousand-gourd standard! That’s a fantastic visual. It’s like a physical representation of his achievements. Any stories related to his famous skill with people, his *jinshin shōakujutsu*?

John: There are numerous accounts of his generosity and ability to remember and reward even minor services. One famous story, often depicted, is his clever handling of the construction of Sunomata Castle (墨俣城) overnight (legend says). While the “overnight” part is likely an exaggeration, his ability to quickly erect fortifications in enemy territory, possibly using prefabricated parts and clever logistics, impressed Nobunaga and showcased his resourcefulness and ability to motivate his men to achieve difficult tasks.

John: He was also known for his **love of grand parties and ostentatious displays**. His Jurakudai palace in Kyoto was famously lavish, and he once held a five-day flower-viewing party at Daigo-ji temple (醍醐寺) shortly before his death, known as the Daigo no Hanami (醍醐の花見), which was legendary for its scale and splendor.

Lila: It sounds like he knew how to throw a party! These details really add color to his personality beyond the battlefield and council room.

Recommended Books / Films / Museums / Historic Sites

John: For those wishing to delve deeper, there are many excellent resources.

For **books**:

- Mary Elizabeth Berry’s “Hideyoshi” (Harvard University Press, 1982) is a comprehensive academic biography.

- George Sansom’s “A History of Japan, 1334-1615” (Stanford University Press, 1961) provides excellent context for the period.

- For a focus on samurai life and warfare, Stephen Turnbull has written extensively, with books like “Samurai: The World of the Warrior” (Osprey Publishing, 2003) and more specific works on battles and figures of the era.

- Eiji Yoshikawa’s epic historical novel “Taiko: An Epic Novel of War and Glory in Feudal Japan” is a fictionalized but hugely popular account that has shaped many people’s image of Hideyoshi. (Note: It is fiction, but very engaging).

Lila: “Taiko” is a classic! It’s long, but it really immerses you in the period. What about visual media or places to visit?

John:

For **films and television**:

- The annual NHK Taiga dramas (大河ドラマ – epic historical dramas) frequently feature Hideyoshi. Older series like “Taikoki” (1965) or “Hideyoshi” (1996) are dedicated to him, while many others covering the Sengoku period will feature him as a major character. More recent ones like “Sanada Maru” (2016) also portray him.

- Akira Kurosawa’s film “Kagemusha” (1980) is set during this period and, while not directly about Hideyoshi, gives a fantastic feel for the era leading up to his dominance.

John:

As for **museums and historic sites**:

- Osaka Castle (大坂城 – Ōsaka-jō) is a must-visit. While the current main tower is a 20th-century reconstruction, the impressive stone walls and moats are original, and the museum inside has extensive exhibits on Hideyoshi and the castle’s history. Visiting here truly helps understand his power base in Osaka. (Osaka Castle Museum official website)

- Nagoya City Museum (名古屋市博物館)**, in his birth province, often has exhibits related to him and other Sengoku figures from the area.

- Kyoto has many sites associated with him:

- Fushimi Castle (伏見城 – Fushimi-jō): Though mostly reconstructions or relocated structures, this was his final residence.

- Hōkō-ji Temple (方広寺)**: Site of his planned Great Buddha statue. The massive bell here later became a pretext for Tokugawa Ieyasu to attack the Toyotomi clan.

- Toyokuni Shrine (豊国神社 – Toyokuni-jinja)**: A shrine dedicated to him. Several exist, with the one in Kyoto being prominent.

- Daigo-ji Temple (醍醐寺)**: Site of his famous cherry blossom viewing party. The Sanbō-in garden (三宝院) designed for the event is still there.

- Odawara Castle (小田原城 – Odawara-jō): Site of his climactic siege that unified Japan.

Lila: That’s a great list! Visiting Osaka Castle seems like the top priority for anyone interested in Hideyoshi. I can imagine how awe-inspiring it must have been in his time, a real symbol of his grasp over the region and its people.

Summary / Closing Thoughts

John: To summarize, Toyotomi Hideyoshi was an exceptionally complex and transformative figure. He rose from the lowest rungs of society to become the unifier of a nation torn by centuries of conflict. His genius lay not just in military strategy, but in his profound understanding of human nature – his *jinshin shōakujutsu* – which allowed him to build networks, negotiate, and inspire (or compel) loyalty.

Lila: His flexibility and communication skills were clearly off the charts. He created a new order, changed Japan’s social structure, and left an indelible mark on its culture and landscape, especially with grand projects like Osaka Castle. But his legacy is also complicated by his later actions, like the Korean invasions and the Hidetsugu incident.

John: Indeed. He was a man of his time, the turbulent Sengoku period, but also a man who profoundly shaped the era that followed. His story is a compelling study in ambition, leadership, political acumen, and the intricate dance of power. He demonstrated how adaptability and sharp social intelligence could overcome immense societal barriers. Even the less savory aspects of his rule serve as reminders of the challenges and temptations that come with supreme authority.

Lila: He’s a reminder that historical figures are rarely just one thing – they’re multifaceted, with strengths and flaws. His ability to connect with people, from daimyō to commoners, especially in a dynamic city like Osaka, and his sheer determination are certainly inspiring, even if we also learn from his mistakes.

John: Well said, Lila. Hideyoshi’s life continues to fascinate because it embodies so many enduring themes: the pursuit of dreams against all odds, the complexities of leadership, and the lasting impact one individual can have on the course of history. As the Japanese proverb says, 「七転び八起き」(*nana korobi ya oki*) – “Fall down seven times, get up eight.” Hideyoshi’s early life certainly embodied that spirit of perseverance.

References & Further Reading

- Berry, Mary Elizabeth. Hideyoshi. Harvard University Press, 1982.

- Sansom, George. A History of Japan, 1334-1615. Stanford University Press, 1961.

- Turnbull, Stephen. Samurai: The World of the Warrior. Osprey Publishing, 2003.

- Turnbull, Stephen. Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Osprey Publishing, 2010.

- Totman, Conrad. Japan Before Perry: A Short History. University of California Press, 1981.

- Sadler, A. L. The Maker of Modern Japan: The Life of Tokugawa Ieyasu. Tuttle Publishing, 1937. (Provides context on the era and Hideyoshi’s contemporary).

- Fróis, Luís. Nihonshi (Historia de Iapam). (Contemporary Jesuit account).

- Osaka Castle Museum. Official Website: [A placeholder, as direct linking might not be feasible, but visitors should search for “Osaka Castle Museum official website”]

- The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 4: Early Modern Japan. Edited by John Whitney Hall. Cambridge University Press, 1991.